FAIRY TALES AND US.

Once upon a time there were two children, sisters, who caught a childhood disease called The Measles. This was in the days before children were vaccinated against the disease so The Measles was a common childhood occurrence. One of the sisters quickly recovered but the other one did not. She knew that she must be very ill because a bed was made up for her in her parents’ bedroom where for several long weeks she had to rest quietly with the curtains’ drawn…This was because The Measles might have some bad effect on the patient’s eyes, the little girl didn’t know what, as they never told her, but the worst thing for a seven year old child was having to rest quietly, day after day, with nothing TO DO.

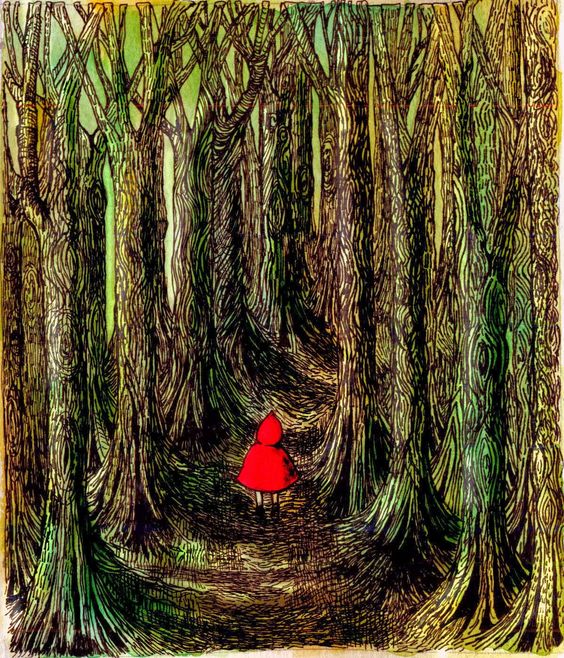

To pass the time, the little girl used to stare at her parents’ antique wardrobe which was made of dark walnut wood with patterning that looked like pictures to her. On one wardrobe door she could see the face of a grinning gnome peering over a stable door, and other whorls and loops seemed like trees in a forest, in which half hidden creatures of the forest gazed into the room. Another diversion was when the little girl’s mother read her a fairy tale from one of the books her father bought her after she became ill. The books were Grimm’s and Hans Christian Anderson’s Fairy Tales, and she spent a lot of the day thinking about what she’d heard. Sometimes she asked for a repeat- reading of one of her favourite stories.

At last she was well enough to leave the dark room and when she got her strength back, escape into the sunshine and play, but she had acquired a taste for listening to fairy tales, not that there were many fairies in them that she came across, and was soon reading them for herself. You probably guessed that the little girl long ago, who was very ill with The Measles was me. And now I’m going to do this post on Fairy Tales.

The Uses of Enchantment.

There’s a book by Bruno Bettelheim, interned in German concentration Camps in WW2, and recognised as one of the important psychoanalysts of the Twentieth Century, that extols the role of fairy tales in helping the development to maturity of young children. The book, ‘The Uses of Enchantment,’ shows how fairy tales help children cope with their own baffling emotions and their feelings of vulnerability and helplessness in relation to the mysteries of the outside world. Since I largely agree with what Bruno Bettelheim has to say about our childhood struggle to understand ourselves and a world that can seem so bewildering to our young selves, herewith, I will give a brief overview of what he has to say about fairy tales.

Children’s Fairy Tales, they’re old folk lore, how old is uncertain, but characters and setting suggest at least the Middle Ages, passed on usually orally and honed in the telling, the setting often the dark forest, the action involving magic and enchantment. The characters are archetypal, the hero, the hunter, the giant, the witch or wicked stepmother, the wolf or some other beast, often capable of speech.

Fairy Tales carry important messages to the conscious or unconscious mind on whatever level the child is functioning at the time, says Bruno Bettelheim, whether ‘experiencing narcissistic disappointments, oedipal dilemmas, sibling rivalries, becoming able to relinquish childhood dependencies, or gaining a sense of self worth, and a sense of moral obligation…’ ([P7.]

It is characteristic of fairy tales to depict an existential problem briefly and pointedly, a problem that the child is experiencing or is likely to experience. This enables the child to come to grips with the problem in its most essential form, whereas a more complex plot would only confuse the child. All characters are typical rather than unique. The figures in fairy tales are not good and bad at the same time, each character is either good or evil and the child learns morality by identifying with one of the characters, making his or her choice based on which character arouses sympathy and not antipathy. The struggles of the hero in fairy tales imprint morality as the hero makes a positive appeal on the child.

Bruno Bettelheim largely applies his analysis to the fairy tales collected by the Brothers Grimm. They’re aptly named, the tales are certainly grim, dealing with the fears of small children concerning the mysterious world, the mastering of their fears and passions, their jealousies and fear of abandonment, their own inadequacies and doubt of being able to cope in that world out there, being central concerns of a child. But what takes place in these stories is a positive outcome. The lone hero figure of the story leaves home, overcomes problem situations, sometimes with the help of other people or animals in the tale, animals, says Bettelheim, often being manifestations of the child’s own most primitive passions and fear of being devoured by them, but in the end he or she gets to live happily ever after, often married to a prince or princess, and there you are, oedipal problems solved!

What is true in the fairy tale can be true in the child’s real life, there’s hope for the future, not the ‘happy ever after’ bit, the child knows that, but the assurance that the child can succeed in life and form satisfying bonds with someone other than one’s own family. There’s always a happy ending to a Grimm’s Fairy Tale.

Much of children’s reading, says Bruno Bettelheim, fails to deliver the message. The primer books from which the child is taught to read in school are designed to teach the necessary skills, irrespective of meaning. Your didactic cautionary tales usually end badly, you get what’s coming to you. ‘The overwhelming bulk of the rest of so -called ‘children’s literature’ attempts to entertain or inform, or both. But most of these books are so shallow that little of significance can be gained by them.’ [p.4]

What is significant, however, Bettelheim argues, is that a struggle against difficulties in life is unavoidable and is an intrinsic part of human nature. The fairy tales collected by the brothers Grimm demonstrate this. It doesn’t matter that the characters and setting are from a different time and place, or create a magical process, the important thing is the existential struggle going on, which no parent can make disappear for the child. Some parents believe that only conscious reality and pleasant, wish-fulfilling images should be presented to children the sunny side of life, but real life is not all sunny, avoiding the harsh events of fairy tales does not prepare the child for life. Woke-ness and warning alerts of distressing content will not prepare children for future life, actually the opposite. But there has to be hope, hence the happy ending

For some parents, however, the happy ending of fairy tales is unrealistic wish-fulfilment, they completely miss the significant message it conveys to the child, that only by going out into the world and forging new relationships can he or she escape the separation anxiety which haunts the child. If we try to escape the separation and death anxiety by desperately keeping our grasp on parents, we are likely to be cruelly forced out like Hansel and Gretel. Only by going out into the world can the fairy tale hero (child) find himself and the other with whom he or she may live ‘happily ever after.’

For this reason, Bettelheim argues that some of the stories by Hans Christian Anderson do not belong to the category of your fairy tale. Stories like ‘The Little Mermaid,’ ‘The Little Match Girl,’ and ‘The Steadfast Tin Soldier,’ are beautiful but extremely sad, they do not offer the feeling of consolation characteristic of the fairy tale happy ending.

Speaking for a seven year old child, or memory of same long ago, I particularly liked some of Hans Christian Anderson’s tales, not ‘The Little Mermaid or ‘The Red Shoes,’ but I especially liked ‘The Snow Queen’ and ‘The Ugly Duckling’. While both stories meet Bruno Bettelheim’s criteria for the fairy tale genre, what I enjoyed in Hans Christian Anderson, was the colloquial voice of the tale teller and the interesting psychology of some of the characters, not that I knew anything about such things at that stage of life, but they stimulated my curiosity. Doubtless I benefited from the archetypal nature of old folk lore, but in Hans Christian Anderson there were those particular situations like the cat and hen story in ‘The Ugly Duckling’ both so complacent and taken with their own significance, yet living in the backwater of the old woman’s cottage. And in ‘The Snow Queen,’ it really shocked me when the little robber girl put her knife to the reindeer’s throat, she was laughing but you knew that she could easily kill the reindeer on whim, even as a child I sensed from this event, that sometimes people could be impetuous and savage like that, as well as sociable at other times.

There were also other lovely touches in Hans Christian Anderson’s tales, for example, the mother duck in ‘The Ugly Duckling’ stating old axioms such as ‘Green is good for the eyes.’ Then there are the strange landscapes in ‘The Snow Queen,’ Kai putting a warm coin to the window to thaw the glass and gaze out at the Snow Queen, and there’s the description of the snowflakes as living beings, I’d say I was appreciating a children’s literature beyond folk lore.

As I remember, what I didn’t like was the surprise ending to ‘The Steadfast Tin Soldier,’ after all his ordeals, so bravely borne his faithfulness to his beloved, the paper doll, having been swallowed in the canal by a fish and ending up in the same room he had started in, only to be thrown into the stove by the random action of a child:

…and he felt himself melting. But he still stood there, steadfast, with his rifle at his shoulder. Then a door opened, the wind seized hold of the dancer, and she flew like a sylph right into the stove to the tin soldier, burst into flame, and was gone. Then the tin soldier melted into a lump, and the next day, when the serving girl took out the ashes, she found him in the shape of a little tin heart.

I didn’t like this sad ending but in adult literature the arbitrary event is not excluded, Charles Dickens uses it in ‘Great Expectations,’ where events are a consequence of a chance meeting at the beginning of the book. Lots of stories and dramas do it, and in life chance meetings or collisions do the same, the truck skewing across the highway and hitting a car, a chance meeting with a homicidal individual, a most unlikely flash flood event resulting in people drowning, are arbitrary events that have occurred in real life Whether children’s literature should include such arbitrary events is debatable, but the deux ex machina is part of adult literature.

As are tragic endings in drama. Shakespeare used them in ‘Macbeth’ and ‘ King Lear’, the main characters being made to face the consequences of their own actions, the only positive for them being their ultimate self knowledge, but too late in their lives. Can’t argue that dark struggle is part of children’s literature. and in books written for the older child. some may not end ‘happily ever after.’ As long as the general direction of children’s stories is struggle towards a positive outcome, children’s literature will continue to help children to mature from their reading, good literature doesn’t follow a woke ‘no suffering’ dictum.

In the best of children’s literature, following on from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, dark events are often part of the tale, even in ‘Peter Pan and Wendy’ there are boys who fell out of their prams as babies and lost their families and in Never-land are pirates who would harm the lost boys if they caught them.

Lewis Carroll’s two books, ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and ‘Through the Looking Glass,’ first published in the mid-1860’and early 1870’s, two of the early books of children’s quality literature present a world where a young person leaves a familiar world for somewhere new and strange. How many times as a child did I read ‘Alice in Wonderland,’ I didn’t quite understand what was its fascination, but fascinate me it did. ‘Alice in Wonderland was a world where physical laws did not exist, where a child could grow larger or smaller in minutes by swallowing the contents of a bottle labelled ‘Drink me,’ or by eating one ‘side’ of a mushroom And the adults of both books behaved like unruly children, irrational, argumentative and dogmatic, the Queen of Hearts in ‘Alice in Wonderland’ shouting the command, ‘Off with his head,’ at whim during a ‘game’ of croquet, in ‘Through the Looking Glass,’ Humpty Dumpty and The Red Queen both being cavalier about the meaning of words.

Alice’s struggle for meaning is the centre of each of the books. In the arbitrariness of these two worlds, the only good sense come from Alice herself. Here she is conversing with the Red Queen, saying that she would try to reach the top of the hill:

“When you say “hill,”’ the Queen interrupted, ‘I could show you hills, in comparison with which you’d call that a valley.’

‘No, I shouldn’t,’ said Alice, surprised into contradicting her at last: ‘a hill CAN’T be a valley, you know. That would be nonsense –’

‘The Red Queen shook her head. ‘You may call it “nonsense” if you like,’ she said, ‘but I’VE heard nonsense, compared with which that would be as sensible as a dictionary!”

Alice doesn’t get very far in these conversations.

Here are some of the books in children’s literature that conform to the genre of Grimm’s and some Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tales and Lewis Carroll’s two Alice books. There’s ‘ The Secret Garden,’ by Francis Hodgson Burnett, in which two children, helped by a local boy who loves the natural world, heal themselves from problems their parents had brought on them. There’s Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Jungle Stories’ in which a feral ‘man-cub’ lives in the jungle, brought up by animals. There’s ‘The Silver Sword’ by Ian Serraillier in which young children survive in World War 11 when their parents become prisoners of war. There’s Roald Dahl’s ‘The BFG, about giants and an orphan girl – and featuring a friendly giant’s strange use of words, and there is also his novel, ‘The Witches’ with it’s challenging ending. A Newbury Award winner, the author Robert C. O’Brien also write two books in the genre, ‘ Mrs Frisby and the Rats of Nimh,’ about lab rats that become very intelligent, and ‘The Silver Crown,’ with its surreal plot of evil forces emanating from a black crown, something like the ring in Lord of the Rings.

All these books with their themes of good and evil or other survival concerns make absorbing reading, even for adults. But there’s another kind of literature for children that you shouldn’t overlook and that’s the kind of delightful world you find in the children’s books ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ by A.A.Milne and ‘Wind in the Willows’ by Kenneth Grahame.

You found this kind of lovely fantasy in Shakespeare’s ”Midsummer Night’s Dream,’ part fairy tale and with actual fairies in it, and you find it, sort of, in Dylan Thomas’ ‘Under Milk Wood’.

Only you can hear the houses sleeping in the streets in the slow deep salt and silent black, bandaged night…Only you can see, in the blinded bedrooms…Only you can hear and see, behind the eyes of the sleepers, the movements and countries and mazes and colours and dismays and rainbows and tunes and wishes and flight and fall and despairs and big seas of their dreams. From where you are, you can hear their dreams.

You hear the dreams of people with these names: The sea captain, Captain Cat, Mr Pugh, Gossamer Beynon, Dai Bread the baker, Mrs Ogden Pritchard, Miss P rice, Willy Nilly, Nogood Boyo, and more. Oh what dreams they have!

What delight can come from such flights of fancy by humans. In children’s literature too. How enjoyable it is when Pooh Bear and Piglet build a stick house for Eeyore the donkey in ‘House at Pooh Corner’ and Ratty goes on a picnic in ‘Wind in the Willows.’ Alice in Wonderland delights us too. There’s that Caucus Race where the animal critters swim in a pool of the tears Alice cried in one of her growing phases. There’s the mouse’s tale, probably the child’s first experience of a concrete poem as in my case it was, – and there’s the Lobster Quadrille:

Will you, wo’n’t you, will you, wo’n’t you, will you join the dance,

Will you, wo’n’t you, will you, wo’n’t you, wo’n’t you join the dance?

Like a horde of children before and after me, we did join the dance in spirit, thank goodness for that! There’s so much to enjoy and engage with in children’s literature, a precursor to Shakespeare and Chaucer and Thomas Hardy and…

Another excellent piece, beth, I’ve recommended it to my daughter who has a toddler who islikely to be a voracious reader.

This Child is blessed.

🙂

Ah, such a good read, my serf.

U has maid my day, mye toff. )

Beth, I’ve just posted this on my FB page, which has a variety of readers worldwide, with the comment: If you have a young child, niece, nephew or young family friend, you might find my friend Beth the Serf’s blog on children’s stories of interest. Quote: “What is significant, however, Bettelheim argues, is that a struggle against difficulties in life is unavoidable and is an intrinsic part of human nature. … the important thing is the existential struggle going on, which no parent can make disappear for the child.”

Thank you, Faustino, for posting on your FB page . What you say here is true, seems to me:

“What is significant, however, Bettelheim argues, is that a struggle against difficulties in life is unavoidable and is an intrinsic part of human nature. … the important thing is the existential struggle going on, which no parent can make disappear for the child.”

This is a really good post, beth. Bettelheim was quite perceptive.

One of the books we had for the 4 of us kids growing up was, A Child’s Garden of Verse, with suitable, whimsically drawn illustrations for each poem.

It contained all the rhymes that English speaking children typically learned; cultural touchstones and most had a short, pointed moral.

For example:

Simple Simon met a pie man

Going to the fair.

Said Simple Simon to the pie man,

“Let me taste your wares.”

Said the pie man to Simple Simon,

“Do you have a penny?”

Said Simple Simon to the pie man,

“No I have not any.”

The illustration was of a sad, hungry, Simple Simon and the pie man with stacks of pies.

The lessons for a child were things in life aren’t free; there’s no free lunch. Also, some things are beyond your means; earn what you need to get them or be satisfied with what you have. Earn a little money and you can have pie!

There’s Jack and Jill – be careful.

Sing a song of sixpence (4 and twenty black birds) – Sometimes life is good and sometimes, stuff happens and it’s not fair. Ask the maid whose nose was snipped off by a blackbird while hanging up the clothes.

Jack Sprat and his wife – Sometimes, you can think up a good solution to a problem.

It’s the same point that you are writing about which is helping children grow up and giving them the tools to deal with life as an adult. The ‘Nursery Rhymes’ were just short simple lessons, in rhyme and song so they were easily learned.

.

.

.

.

Nowadays, I’m seeing too many parents abdicating their job of being parents and guiding, teaching, and equipping their children with the tools needed to be stable, emotionally healthy adults, capable of raising the next generation.

They mistake providing everything a child wants for providing everything a child needs. Children are tyrants. When parents indulge their wants instead of their needs, things go off the rails.

That’s when the parents ask themselves, “Where did we go wrong? We gave them everything they wanted.”

.

.

.

Just a reminder that there were other ways besides the fairy tales to help children grow up. Ohhhhh! Aesop’s Fables! (But I’ll quit now. I’ve gone on enough.)

Agree ,H.R I too read A Child’s Garden of Verse. My sister and I were brought up by a fairly firm dad who instilled it’s lessons. His main message ‘You do not tell a lie.’